'A truth which cried out loud' - first sentences for 'false positives' murders fail to bring justice to families

The Colombian Army murdered thousands of civilians and framed them as guerrillas, claiming them as combat kills for benefits and bonuses - my latest for DG on the ongoing battle for justice & dignity

For Issue #54 of Delayed Gratification magazine, I travelled across Colombia, meeting relatives of those murdered by the state during the civil conflict.

In March, the first sentences were given to soldiers who participated in Colombia’s ‘false positives’ scandal: the systematic kidnap, murder and framing of thousands of innocent civilians in return for bonuses, holidays, and promotions - offered by the government.

I met some of the women whose bravery and determination have made this historic reckoning possible, to hear how far they’ve come and what still lies ahead.

You can buy the magazine here, click here to read the PDF, or read an extended version of the article below.

“A truth which cried out loud.”

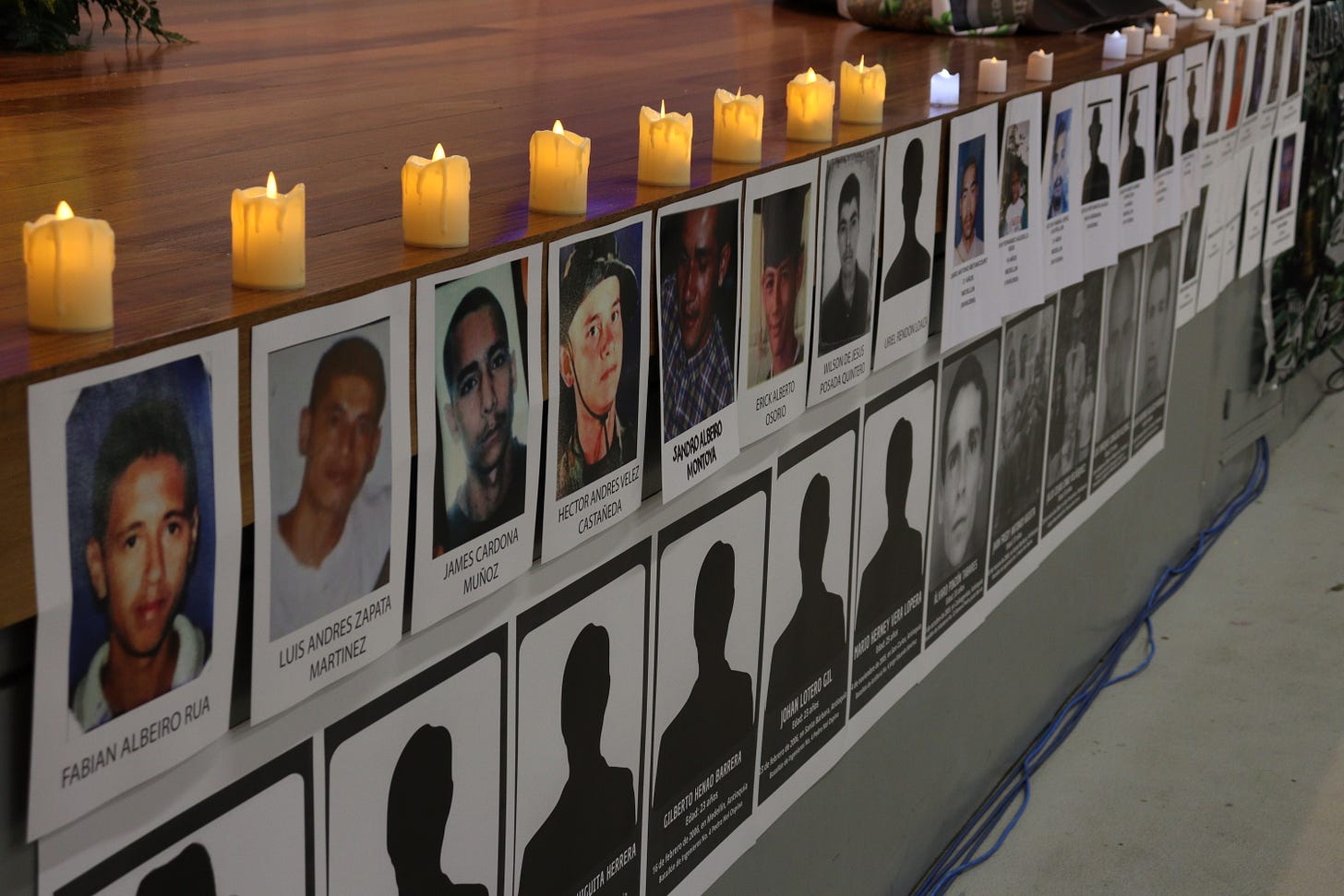

Photographs of young men are being taped to the walls as a pair of robed magistrates take their seats at Colombia’s Peace Tribunal. The pictures are slightly crumpled, having been stuck up over and again during the long search for justice.

The names of the men in the photos are read out loud, each met with the chant, “Present, present, present,” as family members stand and hold up candles, their light a little lost in the brightly-illuminated space, a museum auditorium converted to a courtroom.

Photo: Emily Hart

Suraime Rueda takes the stand, her t-shirt printed with a photo of a young man smiling, squinting in the sun: her partner, Josue, . Before she speaks she pauses, closes her eyes and slows her breath. Hand trembling, she takes a sip of water and begins. “It was the 26th of March 2006. We were together celebrating our daughter’s first birthday, swimming in the river outside our friend Mauricio’s house.”

That afternoon, Josue and Mauricio went to pick up a friend from a market here in Medellín. Neither came back.

“They weren’t the type to disappear or drop out of contact, especially on a day of celebration,” Rueda tells the court. “So Mauricio’s girlfriend and I got up early the next morning to go looking for them: at the market, transport stations, hospitals. Nothing.”

“Our last resort was the morgue. They said there were no unidentified bodies, just two combat kills – guerrillas killed in another part of Antioquia – so we felt calm.”

But in the morgue, they were shown forensic photos.

Photo: Nicole Acuña / JEP

“Then we realised. The ‘combat kills’ were Josue and Mauricio. We couldn’t understand what had happened.”

At the time Colombia was locked in a bitter civil war. “Our partners weren’t guerrillas. They weren’t violent people,” says Rueda. Though she didn’t know it then, she was pregnant. Their son, Josue Junior, is now 17 years old.

Witness after witness takes the stand. Each of their stories is uniquely devastating, but all follow a clear pattern. Someone goes missing and is later found in a morgue – or worse, already in a grave marked ‘NN’ for ningún nombre, no name. They are, to the bafflement of their relatives, registered as a combat death – a guerrilla killed by the army in battle. But sometimes the boots of the deceased are on the wrong feet, the rifles they supposedly died holding have barrels full of mud, or their uniforms are freshly ironed - free of gunshot holes even while their bodies are riddled with bullets.

The explanation is grimly familiar to everyone here: between 2002 and 2010, the Colombian army murdered thousands of civilians, passing them off as guerrillas or members of armed groups. In exchange for these ‘combat kills’, soldiers received bonuses, holidays and promotions.

This has come to be known as the ‘false positives’ scandal. Today’s hearing will collect testimony under ‘Case 3’ which is progressing piecemeal across the country, investigating and charging military personnel - and complicit civilians - for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Photo: Nicola Acuña / JEP

The relatives have fought for over a decade to clear victims’ names, while suffering the stigma of the false accusations. “The media all repeated what the military said about our partners, so we were accused of being insurgents too,” Rueda tells the magistrates.

“They killed so many people. My neighbour was also taken: a hardworking boy who sold avocados to support his mother.”

When the scandal broke in 2008, a few hundred victims were reported. The estimate crept up to 2,000 over the following decade. Then, in 2021, the Peace Tribunal (known by its acronym the JEP) released a new figure: 6,402.

This number has become an emblem of fury, graffitied on walls and tattooed on arms alongside the image of a cockroach in protest at how the Colombian state treated its own citizens.

Photo: Emily Hart

***

***

“The real number is closer to 10,000,” says police-colonel-turned-researcher Omar Rojas Bolaños. Following publication of his study on the ‘false positives’ in 2017, threats to his life forced him to flee Colombia for Belgium, dubbed the ‘Traitor Colonel’.

“People who were just walking down the road or waiting for a taxi were taken and killed and ended up registered as missing rather than dead,” he tells me.

“There are thousands of open cases of ‘missing people’ and ‘forced disappearances’ in Colombia – many of those are actually murders, often committed by the state itself”.

The faces on the walls aren’t the only ghostly presence in the JEP courtroom: accused military personnel are watching unseen via video link. Rueda looks down the lens of a camera in the middle of the room, addressing them directly.

“Here we are… the people whose lives you extinguished just for a holiday, for a promotion,” she says. “You made a business out of murder.”

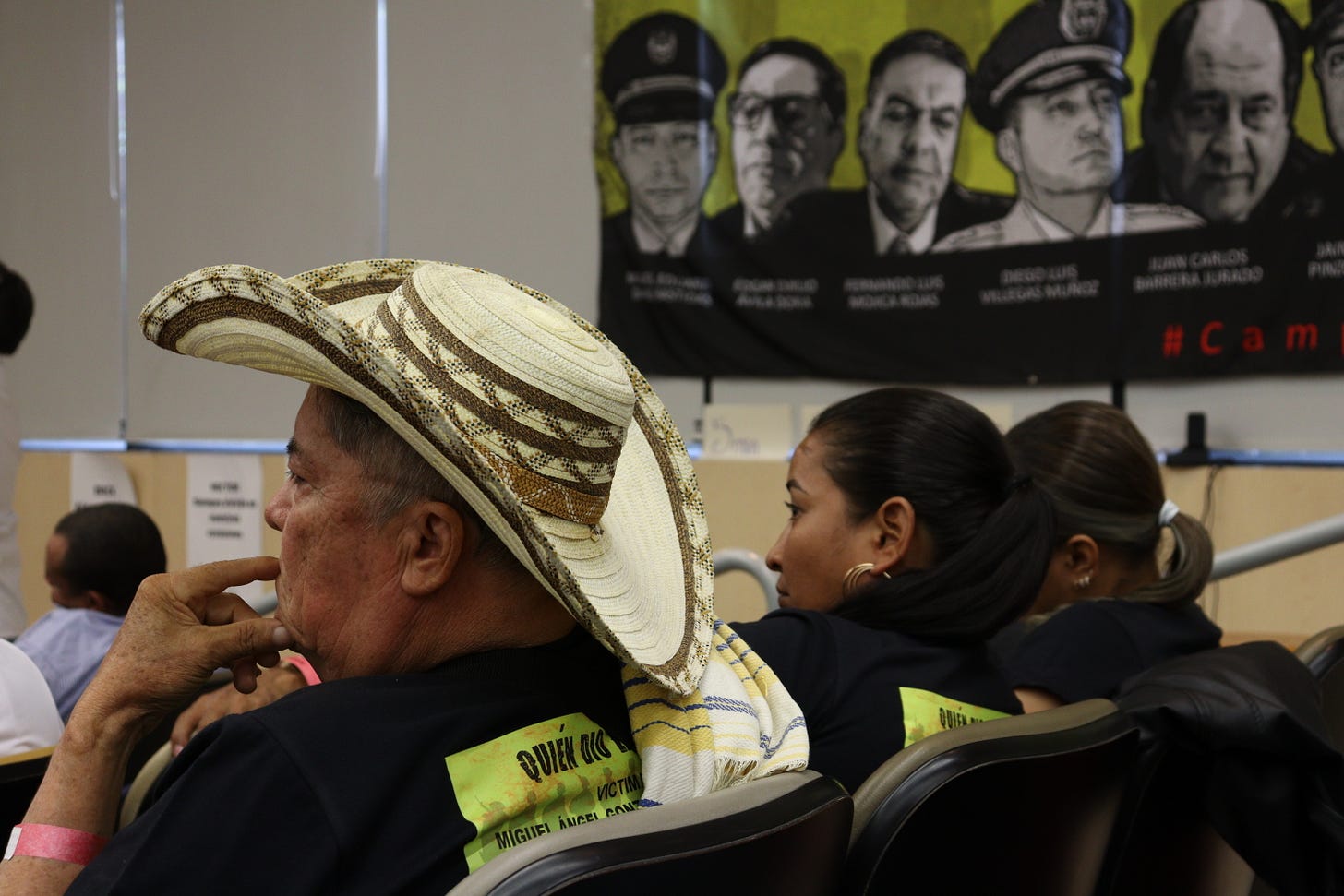

Case 3 has revealed the extent of the inter-institutional complicity which allowed these murders to continue for years, but a poster on the wall asks the question many still want answered –¿Quién dio la orden? ‘Who gave the order?’

Photo: Emily Hart

There has yet to be a ruling on whether these murders were demanded or simply tolerated by the government: the JEP’s investigation has so far mostly dealt with low-ranking soldiers.

Like many across Colombia, Bertina Badillo feels that the investigations have failed to reach the top. “Our families wait for us to arrive with news. What do I say to them?” says Badillo during her testimony, brushing a tear from her cheek with her fingertips.

After her sister was killed by paramilitaries in the north of Colombia, she took the five children left behind, as well as her own, and fled east. There, her nephew Didier was murdered by the army, transported halfway across the country to the Antioquia region and buried as NN.

“Who here has seen justice?” she asks, her forceful gaze directed out into the auditorium. “None of us!” a few call back.

Badillo’s hand is in the air, her thick gold hoop earrings swinging as she points her finger at every other word, jabbing the tense air of the courtroom.

“Almost all these cases happened under President Álvaro Uribe. He denies everything. About the only thing he doesn’t deny is that he was indeed president.”

People start to applaud. A woman shouts “Matarife!” Butcher. Another shouts “And Santos too!” “Bastards!”

Presidents cannot be indicted at the JEP, meaning immunity for Uribe, president between 2002 and 2010. Also protected is Juan Manuel Santos, defence minister between 2006 and 2009 and later president and winner of the Nobel peace prize, awarded for his efforts to end Colombia’s half-century-long civil conflict.

Uribe remains a polarising figure in Colombia: some see his ‘iron fist’ tactics as a turning point in the war, finally forcing the FARC guerrillas to the negotiating table. Others remember his human rights abuses and long-suspected alliances with paramilitary death squads.

Nonetheless he still wields enormous power and has many loyal disciples: he is the godfather of Colombia’s modern right wing, which is still simply called uribismo, with rightwingers known as uribistas.

Photo: Emily Hart

People start to chant, some rising to their feet, fists up, mirroring Badillo: “Justicia! Justicia! Justicia!”

‘Justice.’ They have been fighting for more than a decade, but the struggle isn’t over yet.

***

Rumbling since the start of the 20th century, Colombia’s civil conflict escalated in 1948 with the assassination of Liberal party leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitán. The murder unleashed bloodshed between Conservatives and Liberals all over the country, a period known simply as ‘The Violence.’

In 1958, as a form of peace deal, Colombia’s two political parties created a power-sharing agreement – the National Front. But to some it looked like the elites consolidating their hold over the country, and leftist guerrilla groups formed in the 1960s and early 1970s in response.

They quickly began to take control of swathes of Colombia and in turn were targeted by ‘self-defence’ militias and counterinsurgency paramilitaries. In the 1980s and 1990s, a new generation of these right wing paramilitaries gained unprecedented power, underpinned by close links to the military, the government and certain drug cartels.

By the end of the 20th century, with cocaine revenues bolstering both sides, Colombia was engulfed in a vicious multi-polar war. In 2002, at the peak of the violence, more than 25,000 people were killed.

Álvaro Uribe swept to the presidency that year on a mandate of annihilation, having campaigned against peace talks with the FARC, the largest insurgent group, and instead promising military victory.

The tip of his spear was his ‘Democratic Security’ doctrine: a massive expansion and modernisation of the Colombian armed forces, and a McCarthyist frenzy regarding the ‘internal enemy.’

“The internal enemy was no longer only those who had taken up arms: anyone who dared to propose alternatives or change was stigmatised, risking becoming a military target who had to be ‘liquidated’,” says Rojas Bolaños, the former police colonel.

Under ‘Plan Colombia’ and ‘Plan Patriot’, the US funded much of this new chapter of violence. The battle against insurgency was re-framed as a ‘war on terrorism’ to fit prevailing US foreign policy objectives under George W Bush, having previously been a ‘war on drugs’ and, further back, on communism.

With so much foreign funding and so many promises made, demonstrating success became paramount and a fetish for ‘results’ emerged – along with incentives to create them. Statistical gains, especially tallied in combat kills, helped to make the war effort look like a success.

Although not codified by the government, what emerged was a de facto adoption of the US’s unofficial Vietnam doctrine: the body count policy. This, as then defence minister Santos himself put it at the Truth Commission, was the “original sin, which ultimately gave rise to these atrocities.”

Soon enough, it didn’t matter which bodies were being counted. Men, women, and children with no links to guerrilla groups were murdered and passed off as slain insurgents, in an environment of near-total impunity.

***

In the frenzied atmosphere of the civil conflict under Democratic Security, the army’s perfect storm of pressure, benefits, and hyper-violent training was unleashed on Colombia.

"We used to sing anthems about killing guerrillas while jogging and training in the mornings: ‘Come out, come out guerrilla, we will drink your blood.’ That was the training - it was constant. By the time you went out into military operations, you were practically a hunting dog,” former sergeant José de Jesús Rueda Quintero told the JEP.

Soldiers were bribed, coerced, and indoctrinated into committing massacres of civilians, boosting the stats of their battalions as well as of Uribe’s offensive against insurgency.

“Bring me kills, not problems” went the command mantra of the era, often attributed to one of the most notoriously bloodthirsty generals in the Colombian army, Mario Montoya.

Montoya commanded the much-feared Fourth Brigade in Antioquia during the peak of killings in the region: many soldiers have testified that he demanded ‘litres,’ ‘fountains’, ‘streams’, ‘rivers’, ‘barrels’ and ‘tanks’ of blood.

As Montoya was promoted and his power extended across Colombia’s territory, so did the extent of these killings. He rose to command the entire Colombian army. The pressure was intense: battalions were encouraged to compete, ranked according to numbers of kills, with quotas and targets. Much of this was communicated via radio, managing to leave no paper trail.

Those who refused to deliver combat kills risked demotions, transfers to dangerous regions and even extrajudicial execution.

The murder of innocent civilians was also lucrative for soldiers, and alongside hefty cash rewards, there were promotions and time off. Some battalions saw spikes in killings before Mothers’ Day, from soldiers hoping to go home to their families.

Photo: Emily Hart

"We were exalted: we had power, and it clouds your vision,” one lieutenant, speaking anonymously, told the Truth Commission.

“Producing combat kills and receiving decorations for it, you start to think these people's lives are worthless and nobody’s going to mourn them. This is a gigantic horror story – a book that you squeeze and blood comes out. We didn't care about anything. We didn't care about people’s lives.”

The killings relied on complicity between state bodies, as well as alliances with non-state actors. Within battalions, specialist units formed with assigned roles including collaborating with forensics and police to falsify reports, and liaising with paramilitaries to coordinate the delivery of victims, sometimes dead, sometimes alive.

Many commanders claim they were unaware of the murders of innocent civilians, although soldiers from across the country have testified that it was common knowledge. One told the JEP that it was “a truth which cried out loud.”

“From the newest soldier to the complicit civilians to the battalion commander – they knew how these combat kills were brought about,” former second lieutenant Cesar Augusto Cómbita Eslava testified at the JEP.

Simple though ‘false positive’ sounds, it encompassed numerous crimes, including abduction, murder, framing and defamation. Also vital was the destruction of evidence and obstruction of justice: documents were burnt to prevent the identification of victims and bodies were carried long distances on horseback, in trucks and even in helicopters, reported as NN to stop families finding them.

‘Legalisation kits’ were put together ready to use on dead bodies: guerrilla uniforms, weapons and the rubber boots which became emblematic of armed insurgency in Colombia. Soldiers would go to an empty field and fire their weapons into the air before planting dressed-up bodies there, to trick passers-by into thinking they’d heard a battle – and so that their ammunition levels and the bullet casings at the scene would suggest the same.

The crudeness of the military’s macabre theatrics is testament to the atmosphere of near-total impunity in which it operated. Anyone who tried to report unjust killings was dismissed, stigmatised as an enemy collaborator, or threatened by the army.

The small number of commanders who were placed under investigation for these killings were consistently promoted. Even the few soldiers who were dismissed after being implicated were routinely re-hired in other capacities. Uribe and military commanders claimed that the cases which did emerge were isolated examples of low-ranking soldiers gone rogue: ‘bad apples.’ Many still make that claim.

But soldiers were murdering civilians and being rewarded all across the country, from the forested ridges of Antioquia all the way to Casanare, where the Andes give way to the plains which stretch out eastwards to the Venezuelan border.

This region suffered more ‘false positives’ per capita than any other department of Colombia during the height of the phenomenon. More than 60 percent of the ‘results’ of the 16th Brigade, which covered Casanare between 2005 and 2008, were actually murdered civilians; some former soldiers have testified that it was closer to 90 percent.

***

***

In the tiny town of Aguazul in Casanare, William and Magdalena Acero, a brother and sister in their 40s, sit in the shade of their terrace. Chickens pick around the slim trunks of banana palms and papaya trees in their garden and a trio of perfect Pomeranians chaotically scamper about at our feet – three generations of the same family, Magdalena tells me.

“Our brother Roger lived here with my children and me,” she says. “One day, some guys came to the house asking for directions. They left and came back five times, saying they couldn’t find the address. So Roger went with them to help them find it.”

“Afterwards, he was going fishing at mum’s place. The day passed, then the next. No sign of him, so I rang mum to ask if he was still there. But she told me he had never arrived.”

“I went to the police, who said there had been ‘combat kills’ nearby – they showed me the report and it was my brother, holding a grenade and a pistol, dressed in camouflage.”

Photo: Emily Hart

The family were, she explains, in shock - Roger suffered chronic osteomyelitis in his right leg, meaning that he could only walk short distances at a time. “”How? A disabled person? He was on crutches… I couldn’t fit it all in my head. It was so illogical.” It was years before the Aceros found out that their brother’s murder fitted into a broader catastrophe.

“Everything was hidden back then. We didn’t know it was a national pattern, so many institutions were involved,” says William. “Even now, we don’t feel safe here.”

Civilian or paramilitary ‘recruiters’ identified and even groomed victims whom they codenamed ‘sacks of potatoes’ - items that were ready to be ‘collected’. “It was all planned. Those guys had been making friends with him for a month, winning his trust so that he’d go with them. They later called the battalion to tell them ‘the packet’ was ready,” says Magdalena, shaking her head, her disbelief undiminished by the 17 years since her brother’s murder.

In cities, people were lured to remote areas with fake offers of work, while in the countryside many were simply dragged from their homes, often in front of their families. Roger was targeted because he was disabled, part of the narrative which William and Mary say is underreported.

The targeting of ‘packets’ reflects some of Colombia’s most embedded prejudices: those outside of the conventional social order and those who challenged it were made targets, from community leaders and working-class youth to unhoused, disabled and substance-addicted people.

The UN has reported that these murders overlapped with “efforts at ‘social cleansing.’”. At JEP hearings some soldiers have admitted to deliberately targeting groups on the fringes of society including rural subsistence farmers, who were heavily stigmatised as guerrilla collaborators and consequently suffered brutal state violence.

“During the government of Uribe, we saw extensive collaboration between paramilitaries, army and multinational corporations – particularly the many petrol companies we have here. Farmers were violently displaced, stigmatised and murdered – often accompanied by land grabs,” says Ninfa Cruz, cofounder of local social organisation Cospacc.

Private companies were allowed to finance units under a new law introduced in the 1990s, in exchange gaining special protection of private infrastructure. Companies including BP – which denies all knowledge of false positive killings – funded units later found culpable at the JEP, as did the US government: 47 percent of the ‘false positives’ registered in the peak year of 2007 involved US-financed battalions.

The stigma suffered by those left behind by these killings in Casanare was fierce: elderly people were left unsupported in their villages, work and friendships were lost and children were shunned after their fathers were killed and framed as insurgents.

“Companies shut their doors on me, it was hard to find work. They called us guerrilla,” says William. “Eventually the whole family had to leave town but, even then, I still got menacing phone calls,” adds Magdalena.

Photo: Emily Hart

Roger was buried in a mass grave in Aguazul, his relatives prevented from giving him a proper funeral. “They buried him as NN, even knowing he had family. They wouldn’t let us into the cemetery to see him,” says Magdalena, her voice cracking. “But I kept going, saying ‘that’s my brother.’ If I saw soldiers, I had to run.”

It was a long struggle to get Roger’s remains removed from the mass grave and returned to the Aceros to give him a dignified burial and a marked resting place – particularly important in Colombian culture.

“It took two years to get Roger’s remains back,” William tells me, “They were delivered in three black rubbish bags, as if he was an object – as if he was a piece of meat.”

***

***

After years of killings, the dam finally broke. In 2008, the army abducted 19 youths from the same neighbourhood, Soacha, near Bogotá, reporting them as combat kills hundreds of miles away and burying them as NN near the Venezuelan border.

The ‘Mothers of Soacha’ mounted a campaign and the story hit the front pages. It was a tipping point, and there was an explosion of realisation and outrage across Colombia.

“Seeing that it had happened to other families too, all over the country – often vulnerable families, it was gut-wrenching, disgraceful,” Magdalena tells me. Measures were taken against the system of incentives for combat kills and ‘false positive’ murders dropped dramatically. But justice was scarce for those left behind.

Still claiming it was just a few ‘bad apples’ who had pursued the policy, the army dismissed only 27 men. Montoya resigned as army chief, and Uribe sent him to the Dominican Republic – as Colombia’s new ambassador.

The small number of soldiers who were investigated were mostly sent to military courts which ruled in their favour, lost evidence, or refused to pass cases on to regular courts, even when the constitutional court ruled that the military never had jurisdiction in the first place.

In 2010, when Uribe’s second term came to an end, his former defence secretary Juan Manuel Santos was elected president. In 2016, a peace deal was signed with the FARC, ending half a century of conflict which had left 800,000 people dead and 200,000 missing.

Conflict against and between the numerous remaining armed groups continues to this day, particularly in Colombia’s countryside, but peace with the FARC led to a huge drop in violence.

The JEP was born of that peace deal, with Case 3 opening in 2018: public hearings finally vindicated families’ claims of their relatives’ innocence, and revealed one of the worst atrocities of the long conflict.

Four thousand army personnel have been accepted as witnesses by the court, and 800 soldiers have given testimony so far. Contributions have ranged from admitting that the murdered were innocent to giving the details of killings and the location of mass graves, from which remains are still being exhumed and returned to their families.

The JEP also holds mediated meetings between victims and perpetrators: last year, Marcela Cediel, accompanied by her now 18-year-old daughter, faced the man who killed her partner Leonardo.

“I said to him, ‘Look at me, I have carried your face in my head for ten years, but you don’t know me. Now I want you to live with my face – and my daughter’s – in your mind.’ He started to cry,” she tells me.

Many soldiers say that these meetings helped them confront the reality of the crimes they committed, and many families have said that they have more peace now that they have the truth. “He came to us to ask forgiveness,” says Cediel. “I said, ‘Don’t ask me for forgiveness, ask my daughter – you killed her father.’ He turned to her, and she took his hand and said, ‘It’s ok. I forgive you.’ I was so impressed by her.”

Once hearings and investigations are complete, conclusions and charges are published. If defendants accept the charges, they will receive a non-custodial sentence. If they deny them, their cases are transferred to the JEP’s Investigation and Accusations Unit, where they could face 20 years in prison.

Montoya’s case is now with that unit, after the former commander denied charges of crimes against humanity at the JEP, and even tried to have the entire investigation annulled on the grounds of infringement of his right to justice.

In Casanare, 23 perpetrators have now accepted their responsibility in front of the court, including the former regional director of the intelligence agency, a major general and two civilian informants. Their sentences have yet to be defined, but they will avoid prison in exchange for the accounts they have given.

“I met the man who killed my brother Ferney at the JEP, but I felt like he was only there to avoid prison,” Nancy Calderón tells me. “He’s free. I sometimes run into him at the shopping centre right here in town.

Photo: Emily Hart

“Even now, they call us liars. People think Uribe brought peace to Colombia. But underneath that ‘peace’ were families like ours – and so many deaths,” Nancy says.

Nancy, William, and Magdalena, as well as numerous witnesses before the JEP, say their relatives were tortured, but that soldiers refuse to admit it even when bodies show broken bones, burst eyeballs, or even numerous bullet wounds to the testicles. These allegations have yet to be addressed by the court, but would throw the type of sentences being received by perpetrators into even starker relief.

On 13th March 2024 Roberto Carlos Vidal, president of the JEP, announced the first reparation project, Siembras de vida (Seeds of Life). The first soldiers who accepted their charges will be sentenced to part-time work in environmental restoration: participants will plant trees and tackle invasive species in the mountains around the town of Usme, south of Bogotá.

Other sentences for ‘false positives’ murders will include part-time community work, searches for missing persons and landmine removal. Though these kinds of sentences are an incentive for contributions to historical truth, there is a sense of shock about quite how lenient they are.

“How can the taking of a life be repaid by planting a tree?” asks Cediel.

***

***

For some, justice is neither found nor sought in a courtroom, and holding perpetrators accountable is less important than telling the story in hopes of avoiding its repetition. Every Friday, mothers of victims meet at the Centre of Historical Memory in Bogotá, a brutalist block that cuts a striking dash against the capital’s perma-grey sky.

The room is piled high with quilting, needlework and painting: the women tour schools and universities across Colombia and as far as Europe, putting on arts workshops to tell their story, even meeting up with the Madres de Plaza de Mayo, mothers in Argentina who were victims of similar state crimes.

Doris Tejada is weaving tiny shoes, one after another. Now in her mid-70s, with a melodic, husky voice, she has a striking tattoo covering her shoulder and upper arm: the portrait of a young man whose nose has the exact shape of hers. Her son, Oscar - murdered in 2008.

“The tattoo was so painful, but they can’t take him away from me now. It gave me a form of catharsis: you can’t let anger take hold of you, it’ll make you ill – it’s a cancer,” she says.

Photo: Emily Hart

The women talk while they paint and weave. They are currently planning a play, entitled ‘Women with their boots on properly’. It opens with each woman calling her son by name and asking, ‘Where are you?’

For a long time, that question consumed Tejada: Óscar’s body was missing for 16 years following his death. But in early May 2024, Tejada’s insistence that the search continue finally led to the discovery of her son’s remains, as well as the identification of more than 60 other bodies of missing persons at the same site, whose families are just as relieved to finally find their relatives. “It’s a triumph, after so many years of searching and waiting… Finally, we did it,” says Tejada.

This small group of women includes some of the original ‘Mothers of Soacha’, who continue to campaign for justice. Now known as the ‘Dueñas de la Lucha’, the Mistresses of the Struggle, they not only forced the story into the headlines in 2008, but continue to insist on the importance of storytelling.

Photo: Emily Hart

Their art workshops and public performances are not only for their own catharsis and healing, but for education of new generations - so important in a country which often seems slow to learn the lessons of its own history.

***

Back in the makeshift courtroom in Antioquia, the Search Unit for Missing Persons is onstage, asking relatives of victims to give DNA samples at a station they’ve set up at the back of the hall. Their “agenda of exhumations” is more efficient if they have samples on file to identify the many ‘NN’ still being lifted from Colombia’s soil.

And there is no shortage of potential samples. The auditorium is full of parents, siblings, and children of victims, ageing further and further from the photos on the walls. The physical effects of grief and the search for justice are clear on those left behind.

“My mother had a schizophrenic break when he disappeared. She still says over and over that she’s pregnant with a boy, that she’ll name him Dario. She runs out of the house, saying she’s seen him, chasing boys who look like him,” says Esther Cilia Betancourt, her younger brother’s face gazing out from her t-shirt.

The baton is being passed down the generations. Many have taken over the fight from their parents, now too ill or tired to keep wandering the labyrinth of transitional justice. For Edison Tobón, it is too late for his grandmother to find out the truth about his mother, but not too late for Colombia.

“It's fight she couldn’t finish. She has Alzheimer’s now. This struggle used up the last of her health and life, looking for a truth she now hasn’t got enough time left to discover. For her it was everything, so it is for me now. Even if she won’t ever know the truth, I want it to be known, and to finish what she started,” he says.

***

***

As these regional investigations draw to a close, magistrates are prioritising the national chapter, which will weave together the regional stories to create a Colombia-wide picture, and maybe even give a specific legal answer to the question of ‘Who gave the order?’

Badillo has no doubt: it was Uribe himself. After her testimony, she and I sit together in the courtyard. “A president swears an oath, but he gave orders to kill, to lay waste to so many civilians.” A pale yellow butterfly flaps around the foliage of the tree we’re sheltering under. She is animated again, this time by optimism.

Along with ten others, she has lodged a case against Álvaro Uribe himself, holding him responsible for the killings.

“Though we are only 11 people lodging the case, we seek justice for 6,402,” she says.

The case is now in an inquiry phase, having been accepted by a Buenos Aires court at the end of last year. “I am going to Argentina looking for the justice which we have not had here in Colombia. The law here is no good,” she says. “For me, justice means Álvaro Uribe facing trial for war crimes,” she says.

Badillo’s battle is not without risk: on the day the case was accepted, she received anonymous threats, and she’s sure her phone is routinely tapped. She knows the size of the titan she is up against, along with his legion of uribistas.

But she won’t be deterred.

“Whether we give up or continue, we’ll still be under threat.” she says. “Uribe still has so much power, but sometimes the truth must simply be confronted.”

Under the principle of Universal Jurisdiction, the allegations brought against Uribe are serious enough to fall under the remit of any national court. Argentina was chosen by Badillo and the others for the success of its own prosecution of its military junta, which committed similar crimes during the state terrorism of the 1970s and 1980s.

After an incongruously spectacular sunset outside – and long closing addresses inside – the hearings in the JEP courtroom come to an end. Each portrait is lovingly taken down and stored, and the room is just an auditorium again, although sellotape streaks are left visible on the walls. But most of the attendees – each seeking and defining justice in their own way – will battle onwards.

“Healing and justice are so intertwined. It has already helped us so much to speak, to find other victims, to join our stories. We had to break the wall, so that we could know that we weren’t alone, that there are thousands of us.”

“There’s power now - they made us victims, but we are united and won’t be silenced any more - absolutely not,” Bertina tells me, with just as much gravitas in private as she had on the stand.

“We’ve taken a first step, and I’m optimistic.” She knows there’s a long road ahead, especially with Argentina's recent election of right wing president Javier Milei, which could cause delays to the progress of the case.

“We have to keep raising our voices and moving forwards,” she says. “If we give up, what do we tell our families?”

Photo: Emily Hart

Delayed Gratification is ‘the world’s first Slow Journalism magazine’ - a quarterly print publication which revisits the events of the last three months to offer in-depth, independent journalism in an increasingly frantic world.

My other work for DG includes this feature about a gay collective in San Rafael, Antioquia, and its survival of the paramilitary occupation - and this interview about Colombia’s 2022 Presidential election.