This week, I dug into an ancient but little-understood phenomenon whose mysteries are only just beginning to unravel: mummification in Colombia.

A groundbreaking new study has revealed the extent and complexity of these rituals, but - as archaeologist Daniella Betancourt tells me - some of the results pose more questions than they answer. From mummified babies to masked skulls, these enigmatic individuals continue to fascinate and confound researchers.

As old as human civilisation itself, mummification rituals have been performed all over the world: from Chile to China, from the Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt to Vladimir Lenin and Evita Perón… And, though chronically overlooked, right here in Colombia, too.

In early colonial Colombia, indigenous spiritual and cultural practices were brutally repressed, and many customs were outlawed under the new Spanish Catholic regime. Though there are some mentions of mummification in the early chronicles of the Spanish colonisation, huge numbers of Colombia’s mummies were destroyed - many even burnt, leaving no trace.

Later, amid the rampant looting of recent centuries, those left in tact were often removed from their graves by tomb raiders who stole gold and artefacts - robbing archaeologists of crucial contextual information.

“They are so silent, but have so much to tell,” says Daniella Betancourt, part of a team at the Universidad Nacional in Bogotá, who have been studying a collection of 36 mummies.

“These mummies which we have been studying are true survivors: they have been through everything: the Spanish, the looters - all of it.”

Some dating back to around 400AD, these remains give us new insights into pre-colonial societies and indigenous history in Colombia: they can reveal a vast amount about life - diet, location, and even health. They can also tell us a lot about death, from funerary rites to beliefs about the afterlife.

The indigenous communities who created these mummies, unlike the Egyptians, did not leave walls covered in written history and explanation. This group of academics is now trying to work out who they were, who mummified them, when, and why.

“You don't mummify someone unless you have a specific intention: it's important to understand that for these cultures, nothing is done randomly,” Daniella explains.

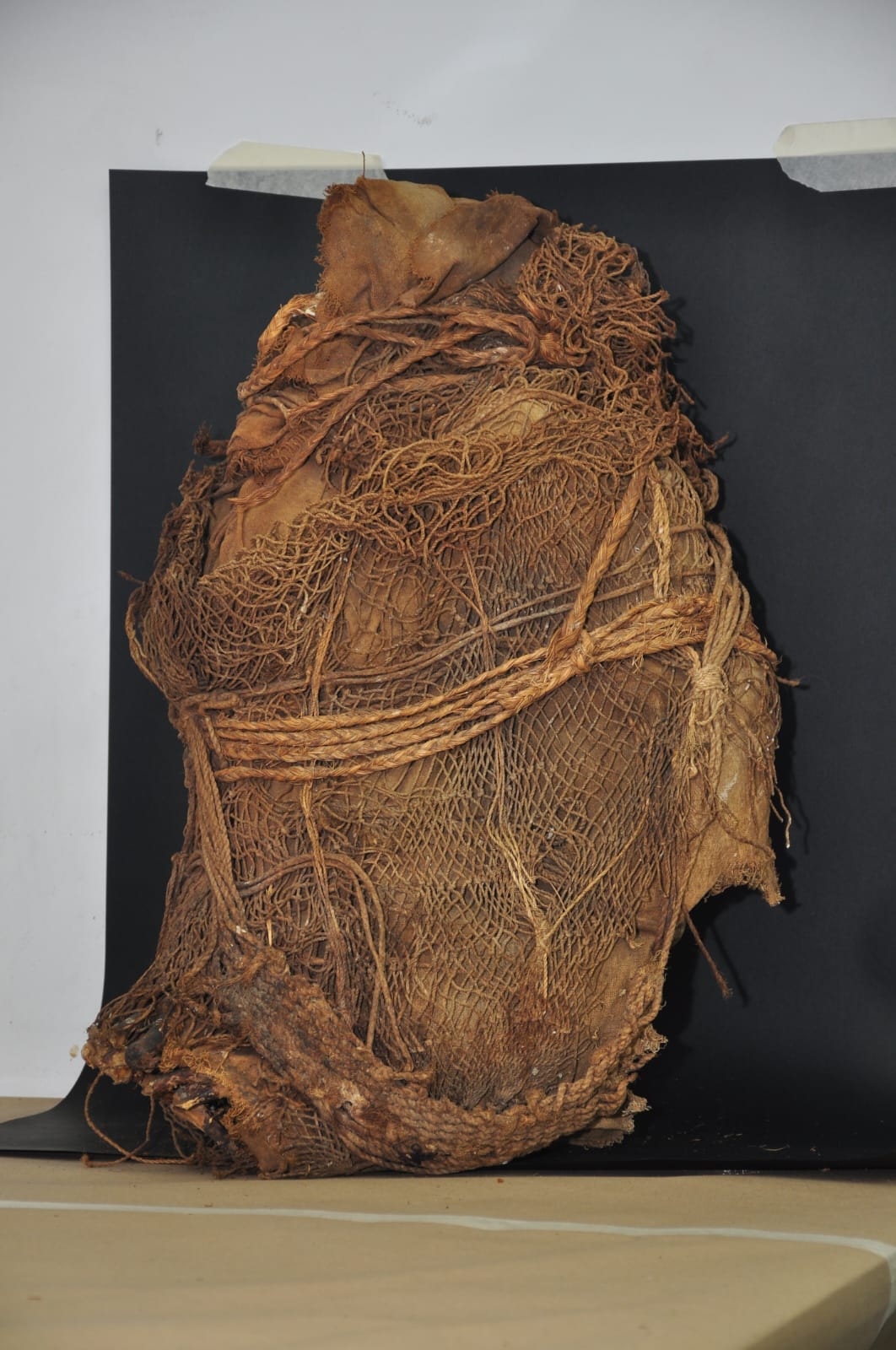

What is clear is that mummification in Colombia was achieved by smoke - bodies wrapped and put over a fire, usually in a seated position. Some historical accounts describe these mummies being left in caves, though this collection is from various institutions which no longer had the means to store or exhibit them - many originally donated by looters who had no use for mummies and - fearing incrimination - did not provide information about origin or discovery.

The Colombian mummification process is similar to that of Peru, supporting the theory that these indigenous groups form part of the same ethnic ‘macro-group,’ who migrated south into the Andes from modern-day Panama, maintaining these customs even as they migrated.

Strikingly, the study shows that this practice was continued long after the arrival of the Spanish - some of the mummies are from around 1700AD.

Under the religious oppression of colonial rule, this would have been a high-stakes act of cultural resistance - perhaps a spiritual imperative, or an attempt to create political or military talismans. With the information available, researchers can still only guess, though there are suggestions in historical records that mummified warriors were carried into battle by Muisca armies.

“All of these cultural practices would have been illegal, so it would even have been high risk to engage in such a practice - an especially a difficult thing to do because it involves bodies and the Spaniards had certain taboos regarding bodies and funerary rites,” Daniella tells me.

“If you were caught mummifying a person, you would have had a hardcore problem… But they continued doing it, which shows that it was very important for them to take that risk.”

Using state-of-the-art scientific methods, the team at the university has been able to reach conclusions about diet, health, genetics, and geography: carbon dating; measurement of nitrogen and strontium - elements which enter bone cells from food and water; and measuring levels of oxygen which reveal altitude and geography.

These tests have shown that mummification was practiced much more widely - by more groups and in more regions of Colombia - than was previously thought.

It had long been believed that only highland and mountain communities - Muisca, Guane, and Uwá groups - practiced mummification, but chemical studies show that some of these remains belong to individuals who lived close to sea level - far from the territories of those groups.

“So, mummification in pre-Hispanic Colombia was not as simple as we thought: it is much more complex and many more groups were doing it - and over a bigger span of time than we thought,” says Daniella.

The range of demographics mummified is also remarkably broad: this collection contains foetuses and children, as well as adult men and women, inspiring a plethora of theories about who was chosen for mummification. Whether these people died and were mummified, or were chosen as human sacrifices specifically for mummification, is still unclear.

“For these same indigenous groups, we have cemeteries and burial practices, so we know that not everyone was mummified: it was a very small group. But by what criteria they were chosen… That’s still a mystery,” Daniella tells me.

Some findings in particular have posed more questions than they have answered: a mummified two-year-old girl was found with a part of her skull removed, the cavity then stuffed with hair and feathers.

“The chemical tests suggest that she was sick, and her binding was also abnormal - but the stuffing is particularly weird - bonkers, even. The removal of a part of her skull is a ritual practice which is especially different from all the rest. We are still working on her to try and understand,” Daniella says.

The collection also contains ten ritual skulls: these skulls were smoked and then had the skin peeled from their faces, before being covered in a thick layer of resin - their eyes and mouths reconstructed from wood, pebbles, and seeds.

Just like those who sought to give faces back to the dead, Daniella says, part of her job is to re-humanise these mummified people - though that work is increasingly controversial.

“There are people who say that if there are no mourners, no family member in charge of the body, that it is not ethical to study them. But you won’t find family members now. I consider myself the chief mourner for these people. I do my work with the aim of re-humanising them, of giving them back their stories: that gives them more humanity than they would get in a storage basement.”

The powerful way that people connect to these mummies and, through them, to history itself is worth the complexity of the study - and the obstacles the team have hit while working on them, Daniella tells me.

“My life changed when I saw mummy for the first time. I felt a really deep connection, like I was looking into the past: a person who lived hundreds of years before me but was still here - not a living person but not a corpse either.”

The next steps will involve using medical scans to see inside the bodies without needing to damage them: Daniella is looking for funding to continue research, and plans to present the recent study at the Cuzco Congress of Mummy Studies later this year in Peru.

“Basically, I am the momentum. I am not going to stop working with them... It’s what I do,” Daniella laughs.

This interview is also available via the Colombia Calling podcast on Spotify, Apple, and wherever else you get your podcasts!

And if you are interested in Colombian archaeology, check out this article & podcast about the ancient statues of San Agustín:

Daniella Betancourt is an archaeologist based in Bogotá: specialising in bio-archaeology and the study of mummified remains, Magister en Antropología de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Daniella is co-author of ‘Variabilidad cultural y biológica de las momias antiguas de Colombia’ (upcoming)- written with Héctor Polanco N. (Facultad de Odontología), José V. Rodríguez C. (Departamento de Antropología), and Andrea Casas V. (Instituto de Genética.)

Share this post