'There is nothing more queer than Nature' - Brigitte Baptiste on biodiversity, sexuality, and healthy irony

💬 Colombia's most acclaimed ecologist - and LGBTQ+ icon

A brief interview with the inimitable Brigitte Baptiste: renowned biologist, Director of the Ean University, and former-Director of the Humboldt Institute.

When we spoke, I was dust-coated and sweltering in the hall of Yopal Airport - fresh off a reporting trip in Casanare and waiting for a flight. Brigitte, meanwhile, was immaculate: sat in her office in Bogotá, sporting a perfect white bob and a green floral dress, along with pink hoop earrings and long manicured nails in an identical colour - all absolutely on-brand for the woman who has become something of a rockstar on Colombia’s eco-scene.

We chatted about the inherent ‘queerness’ of nature and humanity’s place in it, along with optimism, climate change, and the importance of not being earnest… or not always, at least.

You’ve often said that ‘there is nothing queerer than nature’ – you bring a queer perspective to ecology as well as an ecological perspective to gender and sexuality - so how do we unite the two areas to build a better future?

That phrase arose from reflection on recent scientific revelations and discoveries about sexual and gender diversity in what we call ‘Nature’. Nearly all species have individuals - or portions of the population - which display behaviours which are diverse in those terms.

There’s so much discourse about ‘natural’ and ‘anti-natural’ used to condemn behaviour we don’t like. But Nature is queer - that’s been proven - we can actually see that sexual diversity is present.

So that’s the starting point: those arguments regarding ‘unnatural’ etc are not consistent - or acceptable.

But we have to finally recognise that we as biological beings, as species who have evolved, everything we do is natural: our technology, our place in the world – it might not be adaptive, but it’s certainly natural.

So when we talk about nature, we are talking about humanity too; we are part of it, so the dichotomy between culture and nature is false - it can be dissolved entirely.

The idea of ‘intersectionality’ gets discussed a lot in sociology and politics, but not so much in ecology - why is that?

The idea of ‘queer ecology’ was proposed by Timothy Morton about 15 years ago: as an ecologist, I find that there is a direct connection between our biological condition and the kinship we have with other living beings. The consideration of the queer brings us closer to understanding of the diversity which is present in everything – diversity is an evolutionary rule.

Nature changes constantly in subtle ways, it produces diversity in terms of sexuality, in terms of gender roles, in terms of parenting behaviours… Part of evolutionary adaptation is to produce diversity and diverse behaviours.

And we have to accept that in all human activities there is the same phenomenon, we often discuss evolutionary adaptation in terms of ‘bending the path.’ Instead of looking at the economy, politics, technology in straight lines, we should always be bending things a little bit: that’s where innovation and inspiration appear, and where the alternative way is. There is nothing straight in nature.

Are we living through a moment of awakening when it comes to nature and ecology?

I think so – there’s a profound reflection about the link between land and its biodiversity and its people and their rights.

It’s not a perfect reflection, but opens a conversation about the right to construct our own identities, the right to self-determination and autonomy – that self-analysis - how do I experience myself in new ways, from the inside, from my body, and with my symbolic understandings and my languages.

I’m also looking at cyborg ecology at the moment – at how can technology might help us to create sustainability, to communicate with other living beings - or destroy what’s left… Undoubtedly that’ll be the question with AI, even more so with basic technology like drones.

We now have at our fingertips innumerable options to gain conscience of our presence in the world - and re-evolve, replant our place on earth with all our knowledge and skills and feelings. That’s where we are really free - full of possibilities of being.

You told El País that queer theory is ‘a theory of the deviant that, with humour and irony, posits that identity is a fiction full of anomalies’ - do you think humour and irony have been missing in discourse around gender and sexuality, or around ecology and climate science?

Totally – we take ourselves too seriously, and we are very passionate in all the wrong ways.

Yes, we are responding indignantly to discrimination and oppression, fair enough – but it makes it very difficult take a calm position. But I recognise my privilege in my context. I can’t say I’ve felt discrimination or abuse or war myself.

Obviously my transition was difficult for me - the public adoption of my identity as Brigitte at 35 years old.

I took myself so seriously back then… But I realised over time that identity is a performative thing – it can be used as a narrative tool to bring me closer to people, or it can make me an isolated person, sullen and resentful, who feels like my political struggle is the only valuable thing.

This happens quite a bit in the LGBTQ+ community - we start to discriminate against ourselves – who is purer? Who is more gay? More trans? We fall into classic modern problems there, using difference to mark territory instead of to integrate territories.

It’s the same on the left - in any movement which hopes to be renovating, someone ends up assuming the purity of the renovation – this even happens in indigenous nationalism across the region. And that opens space for authoritarianism and more violence.

It happens in science too - you find very universalising perspectives. We’ll never manage to tackle the environmental or social crises we are facing right now if we keep those attitudes. Nobody has a claim to purity - or truth.

We need a little irony, and admiration for one another. It should be joyful!

Anyway, we are going to get weirder and weirder with the climate crisis – people will get stranger and stranger. We will need to adapt to the new and emerging conditions on the planet, and we’ll change our behaviours, our ways of expressing ourselves.

In 50 years, we will be so different from our ancestors – and people in the future will say how mad we were in 2024.

They’ll probably probably be cyborgs by then - hopefully happy ones.

You seem optimistic, but you’ve also written that ‘fire is resolving what politics has been putting off’ – are we already in flames or is there hope?

In Colombia at least, we are having a complex public debate in which you can really see that certain things, unless they are solved, will explode.

They will explode – they’ve been exploding.

If we don’t make better-quality policies, we’ll stay stuck in cycles of armed conflict, drug trafficking, poverty, inequality, injustice. But I don’t see those changes happening right now, not even in environmental terms.

For example, the management of protected areas in Colombia: it’s a farce. Many countries in our continent have national parks which have good-will roots, with conceptualisations of ourselves as modern civilisations, but we fail because we don’t build our own ideas, we try to imitate other countries.

And we fail harder every time. We are losing those areas due to the accumulation of bad or incomplete policies over the last 25 years. And people in and around the areas are just trying to survive - trying to reach tomorrow - national parks mean nothing to them.

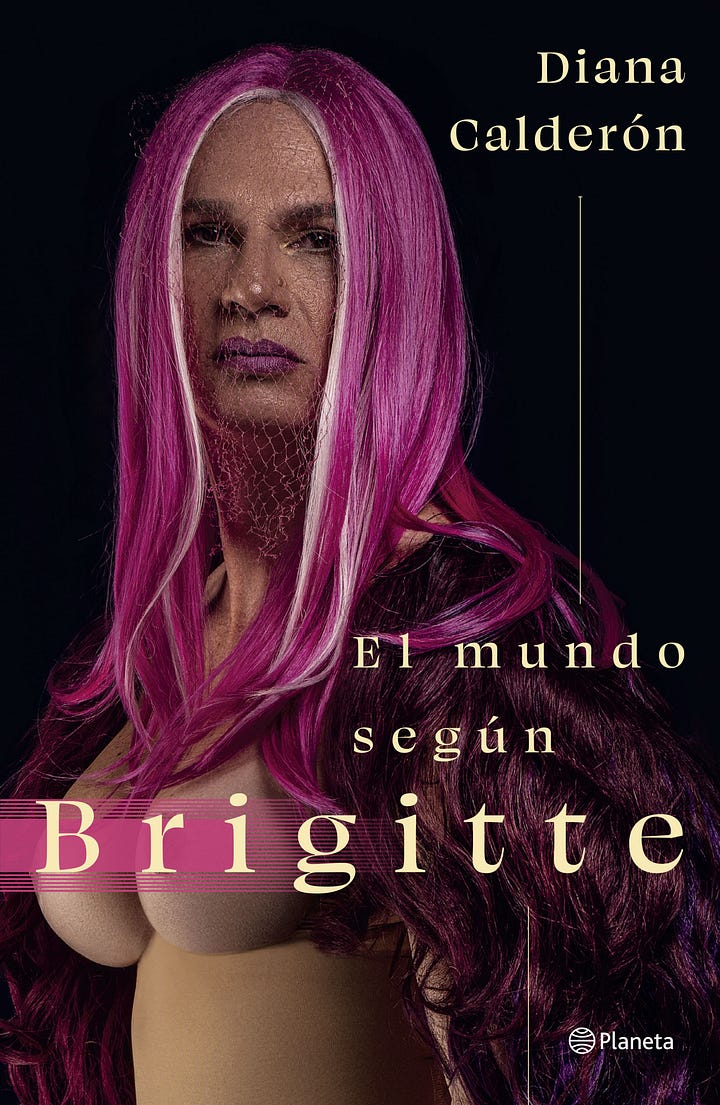

Two books published in the last few years - ‘El homenaje ilustrado’ and ‘El Mundo según Brigitte’ - as well as murals and graffiti of your image - have cemented your status as a Colombian icon. How does that feel?

It makes me happy – I feel honoured! It comes from people I’ve never even met - and it’s so loving towards my words and work.

But I’ve also been the target of a lot of criticism, some of it very violent. A lot of the most poisonous attacks have been online. They even hacked my Twitter.

Weird story actually - I reached out to you on Twitter during that period, and got sent a WhatsApp number. I wrote to it, thinking it was you, but I just kept receiving the same sticker in reply - over and over: a smiling avocado, walking and swinging it’s arms… I was there thinking, “This woman is actually kind of odd…” Months later, I read that you’d been hacked and it started making a lot more sense.

Hahaha - and that’s the very least of it…

I try not to let it go to my head, but it’s weird when people recognise you in the street, or ask for your photo – you realise you’re a public figure without having sought that out – I’m just a university rector!

But of course, whenever I can return that cariño, I’ll be there.

Want more on Colombian ecology? Check out these podcasts -