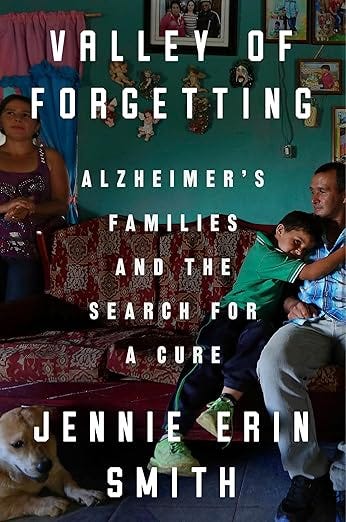

This week, I joined Richard McColl on the Colombia Calling podcast, to interview Jennie Erin Smith about her new book, ‘Valley of Forgetting: Alzheimer's Families and the Search for a Cure.’

The book is a fascinating account of Colombian families - carriers of a genetic mutation which causes early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, some suffering symptoms as early as 40 years old. Jennie’s work recounts the birth of research and the heady mix of hope and tragedy which ensued, as a determined group of doctors and researchers pursued their investigations.

Video & audio here - plus an article (exclusively) here on Substack!

Riding on horseback through a landscape as ridged and folded as the human brain itself, doggedly navigating labyrinthine hills and tangled valleys occupied by armed groups in the midst of Colombia’s civil conflict, Dr Francisco Lopera made an extraordinary discovery.

A remarkably large number of people here, in the region of Antioquia, were suffering dementia symptoms as early as their 40s - many of them from the same family.

“ It's a single genetic mutation, unique to the region of Antioquia, Colombia, that causes the disease in this family of 6,000 people - which is the largest family in the world with that type of Alzheimer's disease,” explains Jennie Erin Smith, whose book on the ‘paisa mutation’ and Dr Lopera’s decades of investigation came out earlier this year.

The book follows Lopera, a Colombian neurologist, and his American collaborator, Dr Ken Kosik over decades of research, discovery, and collaboration. The two provide a pleasing double-act, Lopera an earnest and folksy clinician, Kosik a zany intellectual - both good-natured and admirably dedicated to extremely difficult work.

Researchers not only faced threats within their institutions in Medellín, but the rural areas they travelled to in order to find these families were brutal epicentres of armed group occupation and pervasive violence.

This same violence was a major factor in the lack of understanding around the disease: “What was Alzheimer’s but another way to die, in a place where early death was unremarkable?” Jennie asks.

“The investigators had to leave the University of Antioquia and decamp to the countryside for weeks at a time - and they were constantly being harassed. They were kidnapped. A nurse was kidnapped. Dr. Lopera himself was kidnapped at one point… Swirling dynamics of civil strife, paramilitarism, and guerrilla groups, I mean, this was something that they dealt with all the time - and they still got it done.”

“ I've been thinking about that a lot lately because in the United States, research funds are being just hacked to smithereens by this, this administration - really decimated. I ask myself, can research occur on these tiny budgets? And then I think back to what the Colombian researchers were able to achieve, on grants of $800 - they were able to begin these studies.”

At the heart of this story are the families, to whom the book is dedicated. Their tragedy is an intimate one: many watch their loved ones succumb to dementia in their 40s and die young, not knowing whether the same fate calls from within their own genes.

“For some two hundred years they remained in the hills, farming and reproducing and falling ill and dying without the outside world taking notice,” Jennie writes. The ‘paisa mutation’ has now been traced back to four sisters living in a valley in Antioquia in the 18th Century, “whose fecundity allowed the mutation to take hold quickly, across vast terrain, in a single generation.”

Such a large number of people in one family - thousands of whom would likely be carriers of this genetic mutation - had huge potential for research, and by studying an early-onset manifestation of the disease, senile forms of dementia can also be better-understood. This work is crucial for all of us: some research predicts that 150 million people will be suffering dementia by 2050.

“That really made this family extremely important because when you have that kind of statistical power, everything you find out matters. So in the 1980s and 1990s, there was a lot of attention on this family, but it wasn't until fairly recently - around 2012 - that they began testing drugs on them,” Jennie tells us.

Alzheimer’s Disease - like other dementias - is a devastating but little-understood condition, cures and treatments for which remain elusive even after decades and billions of dollars of research.

This is doubly true in Colombia, where dementia still floats in a cloud of entrenched misconceptions, supernatural taboos, and phantasmagoric explanations - from curses to witchcraft. Many people suffering from dementia have lived out their final days in psychiatric hospitals, their condition understood as a psychiatric issue rather than a neurological one.

‘Valley of Forgetting’ is not only a detailed account of the scientific story of the research and subsequent crenezumab drug trial, it is also an finely-drawn portrait of a family, a country, and a moment in history - the three intricately interwoven.

This disease - much like Colombia and the complex dynamics in which many of its residents live - makes no allowances or exceptions for studies, for family responsibilities, or for hard-won second chances.

“So many of their parents don't have any college at all, so this is a very crucial time in their lives - in their twenties, it's a time when they need to be graduating and they need to be getting jobs. And once they're derailed from that by becoming full-time caretakers, they can be very, very lost.”

The offspring of a carrier has a 50% chance of also being a carrier: a carrier has 100% certainty of developing early-onset Alzheimer’s. Or so it was thought, until the researchers met Aliria.

Despite being a carrier of the ‘paisa mutation’, Aliria Piedrahita was almost without symptoms well into her seventies. She was, it was discovered, the carrier of a gene which came to be known as the ‘Christchurch mutation’ - which could seemingly stave off the effects of the ‘paisa mutation.’

What actually causes Alzheimer’s symptoms is still unclear: brains show a combination of amyloid-beta plaque and fibrous tangles inside nerve cells caused by tau protein: as one researcher told Jennie, “I don’t really know what Alzheimer’s is. And I have been studying this for twenty years.”

In fact, the scientific community has long been in dispute about which of these symptoms is the cause - for decades, the amyloid theory has had hegemony, meaning most of the billions dollars invested into research and drug trials has been to tackle the presence of amyloid in brains. But this theory is increasingly coming into question.

Aliria’s brain was donated to science by her family, and studied after her death.

“She had a head full of amyloid beta - a huge amount of amyloid beta in her brain. And yet she continued to function - because she didn't have so much tau. Tau creates tangles in the neurones that kill neurones, whereas amyloid doesn't appear to have a direct toxic effect on brain tissues. It's all really, really complicated and it's all still being hammered out…”

Another book was published earlier this year by Charles Piller about these two tribes and their warfare: ‘Doctored: Fraud, arrogance, and tragedy in the quest to cure Alzheimer’s’ - the book details deception and distortion of evidence over the years by those who suppose the amyloid theory of dementia. Several have lost their jobs as a result of Piller’s investigations.

“So then the question is, for the Colombians who ended up trying crenezumab - an anti-amyloid drug - were they on some level victims of the same myopia?” asks Jennie.

“And I would say yes and no - at the time that they began this trial, nobody knew any of this. But six years later, you started to get some very disturbing evidence, and then when it failed - which was a sad day that I was there for - no-one was that surprised.“

A troubling dilemma haunts this book - more ethical than scientific: disclosure. Many of the participants in the drug trials never found out if they have the gene - it was considered by Dr Lopera that for the Colombian context, the option shouldn’t even be given to patients.

“It was Dr. Lopera’s specific policy not to tell them. Nearly all of them went on to have families - some of them had pretty decent sized families. A taboo developed around knowing whether you had the mutation or not, and that probably had something more to do with Lopera not really having the money or the means to start counselling programs and do everything you needed to do to tell them.”

Among the book’s more haunting stories is that of Paula: adopted by an American couple as a child, she re-connects with her family in Colombia later in life, only to find out about the genetic mutation carried by so many of the relatives she left behind.

“ Paula was a girl who had grown up in the United States. She was adopted from Medellin as a 9-year-old child who had been abandoned by her mother and was living in an orphanage,” Jennie tells us.

“So she'd had this really tough childhood - and when she came back to visit with her birth siblings, she also had the misfortune of having to learn that there was a disease in the family that could affect her. She was 38 when she made the trip - so it could affect her within five or six years.”

Paula later got tested in the US: she had the mutation.

“But did she commit suicide? No. Did she become clinically depressed? No. She was able to make a series of decisions that have been in my estimation denied the Colombians. She had one biological child and she was going to adopt another, but she was able to make a decision because she did not wanna be in a position of having, you know a five-year-old and becoming ill.”

“So she was able to use that information. She changed jobs to, to have more time with her other child: she did a number of things that the Colombians are denied by being discouraged from seeking that information.”

Clear in the knowledge that effective treatments are far off, to take part in the trial was a selfless act for many of the participants: a long series of days in the clinic, invasive tests, and promises to donate their brains to science.

“ For most of the people in their forties who are, in a position to get sick within the next couple years, they were absolutely not doing this research for themselves,” says Jennie.

“ They were doing it for their kids, hoping that there would be a pharmaceutical option that could extend people's lives - that the next generation wouldn't have to suffer the way they had suffered and their parents and grandparents - and all the way down the line - had suffered.”

The book ends - as this chapter of Alzheimer’s research did - with the announcement of the trial’s failure in 2022: the drug did not have any statistically significant effect. Last year, Lopera himself died aged 73.

Despite the book’s pragmatism and ambivalence about some of the decisions made during the investigation, the reader is left us clear that, regardless of the outcome, Lopera’s legacy is concrete. Through his research and the crenezumab drug trial, he put into place unprecedented infrastructure for Alzheimer’s study in Colombia, and gave the families involved new knowledge and agency.

Unsentimental but deeply human, Jennie’s writing never loses sight of the hard truths which dictate the lives of these families. The tensions of the story are (rightly) left unresolved, as is the devastating mystery of Alzheimer’s - faithful to the dark tones of the grey areas faithfully depicted throughout the book.

Jennie’s writing pulls the reader close to the Colombian families, in particular to the extraordinary women facing tragic odds with dignity and resilience, inhabiting a timeline dense with life-altering events, game-changing discoveries, chaos and loss.

The protagonists - doctors, patients, and carers alike - often feel like twirling leaves in the harsh winds of history, science, and pure chance: this remarkable book gives that tumultuous dance a very real sense of grace and humanity.

Check out the full interview here plus some ‘behind-the-scenes’ on how Jennie wrote the book below!

This interview is available on Spotify via Colombia Calling - as well as Apple and wherever else you get your podcasts!

‘Valley of Forgetting’ is the fruit of years of labour: Jennie shared these insights about the writing and editing process after we recorded the podcast!

You hear a lot about the nonfiction book process as a period of “research” followed by a period of “writing,” and maybe that’s the case if you have a book with a pretty short timeline - like maybe two years - that you can divide neatly like that.

But when books turn into sprawling multi-year projects, as both of mine did, those concepts tend to blur. You’re researching for years on end and you’re writing while you’re researching and you continue to research through the end of the writing process. You’re collecting tons of information that you will never explicitly use but that serves to show you patterns, to allow you to characterize people’s thinking and actions with authority.

The way I catalogue all this is to keep a writer’s diary that is very detailed, talking to myself about all my impressions of what was happening. I’d spend like two days reporting, making notes in a notebook, then spend another whole day dumping all that into the computer and elaborating. I never let more than a couple days pass between the notebook and the computer.

The core of this effort was those diaries. They went on and on from 2017 through 2023. Just Microsoft Word documents that I could order by date. Sometimes I would go back into an entry and add information that I learned later.

The diaries helped enormously in the writing process as well. They allowed for a better sense of urgency in the narrative. And they allowed me to tell stories in parallel – for example the day that two major Alzheimer’s drug trials were canceled, I happened to be with Daniela, my protagonist, who had just seen a geneticist about a test. The news came to me in a text from Ken Kosik, the researcher, saying “bad fucking news.” I could relate all those things at once and it was more dynamic that way.

Whenever I got stuck figuring out how to advance the narrative, I could paste in some paragraphs from the diaries. They made for a good starting point, and they erased any writer’s block, because they were texts already written, so I just had to work them up.

And because this book underwent a really elaborate fact checking process – the journalist Sophie Foggin worked on this with me for nearly a year – they could serve as the first point of reference for her investigations.

There were a lot of debates about paisa expressions. The families spoke practically in dialect they had so many of them. Sophie was helpful in exploring them. One word that came up constantly was “picado,” which the people in the families used to mean that someone had become ill with Alzheimer’s.

I thought it meant bitten or stung, as by an insect. But then it seemed instead to mean rotten – like a flyblown fruit. Neither is a very nice sentiment. I did my best guess with some of these phrases like “eavemaria, así es la cosa, montañero, etc.” Not sure I was right every time.

In the end I kept the original transcriptions as I hope this will be translated into Spanish and no one will have to replace the local terms with generic ones.

In terms of access, there are privacy laws for medical information in Colombia, especially for test results and things like that, but I would say I took advantage of a looser culture with regard to privacy.

Lopera let me have the full medical records for people that had died. That’s how I was able to reconstruct the full story of Doralba Lopez Pineda, whose autopsy I attended and whose daughters became important in the narrative. And it allowed me a little window into how he and his team dealt with the patients and thought about them.

People in Colombia don’t get that much privacy in their daily lives, and don’t have an expectation of it in the clinic either. The walls are pretty thin in those consulting rooms. I would ask the docs if I could accompany them as they spoke with patients, then identify myself to the patients and their families.

I don’t think I was ever turned down. But I took their phone numbers and circled back to them before using the information. I censored some things at their behest.

And really a lot of my time in the consulting rooms was just to understand how things were done and not to explicitly use the information I was hearing.

It was all about finding patterns.

Jennie Erin Smith is a science journalist whose work has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, TLS, McSweeney's, The New Yorker, Undark, and others. She lives in Florida and Colombia.

She is a recipient of the Rona Jaffe Award, a fellowship at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Mass., two first-place awards from the Society for Features Journalism, and the Waldo Proffitt Award for Environmental Journalism.

Praise for ‘Valley of Forgetting’

“In her handling, flat questions about the ethics of medical research are rendered in rich dimension—including, for example, whether to reveal results to study participants who were found to have the genetic mutation that may cause early-onset Alzheimer’s.” The New Yorker

"The book left me aching and enraged. . . . Clinical trials are essential, but we must not ignore the turmoil of the participants - people to whom Smith has finally given identities." New Scientist

"Anyone who still holds a Dawkinsian view of science as abstract and logical should read Valley of Forgetting. . . . a valuable guide." Times Literary Supplement

"Valley of Forgetting reminds us that scientific progress is measured not only in breakthroughs but also through the sacrifices people make, the trust that is built. It is a tender story of the unshakable will to make meaning in the face of inexorable loss--one that begins long before death itself. In her willingness to sit with contradictions--hope and despair, progress and stagnation, science and faith--Smith elegantly captures what it means to love, to belong, to hold on to one another when so much is uncertain." Washington Post

"Jennie Erin Smith writes with such narrative skill, such empathy and curiosity, such a strong sense of the place where science and people meet, that you come out with the feeling of having witnessed an extraordinary investigation into the mysteries of what makes us human." Juan Gabriel Vásquez, author of The Sound of Things Falling

Share this post